The sisters of Lazarus, Mary and Martha, are found in Luke 10:38–42 and John 11:1–46; 12:1–10. Some modern interpreters focus on their gender, imposing traditional gender roles on them, such as Martha’s service as being a good homemaker. Many Christian women in the U.S. may be asked whether they are a “Mary” or a “Martha.” However, a closer look at the text and the interpretations of early and medieval Christians tells a different story.

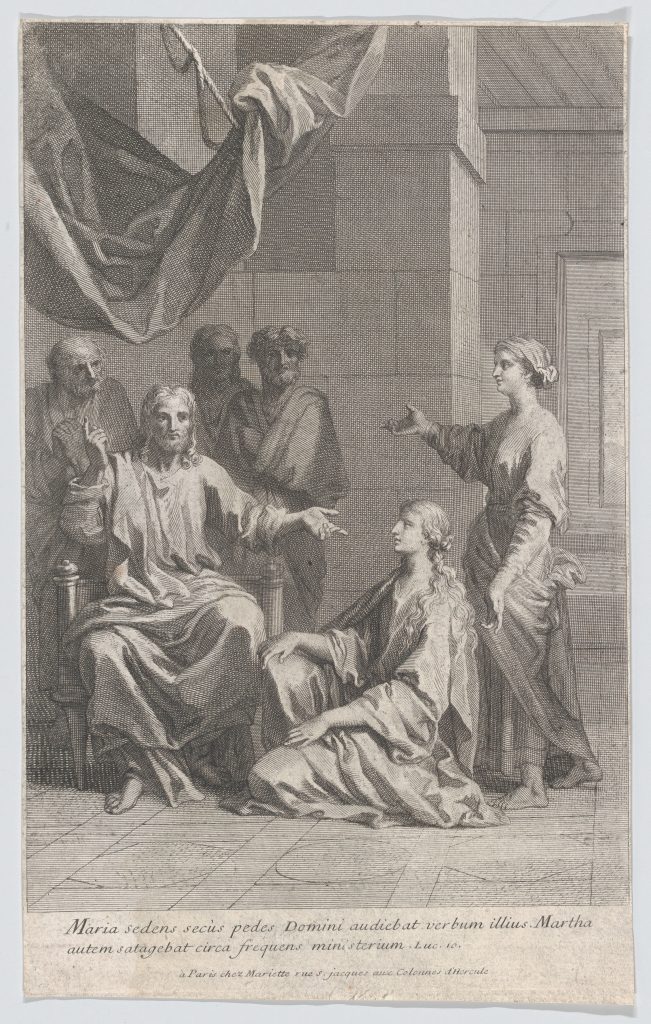

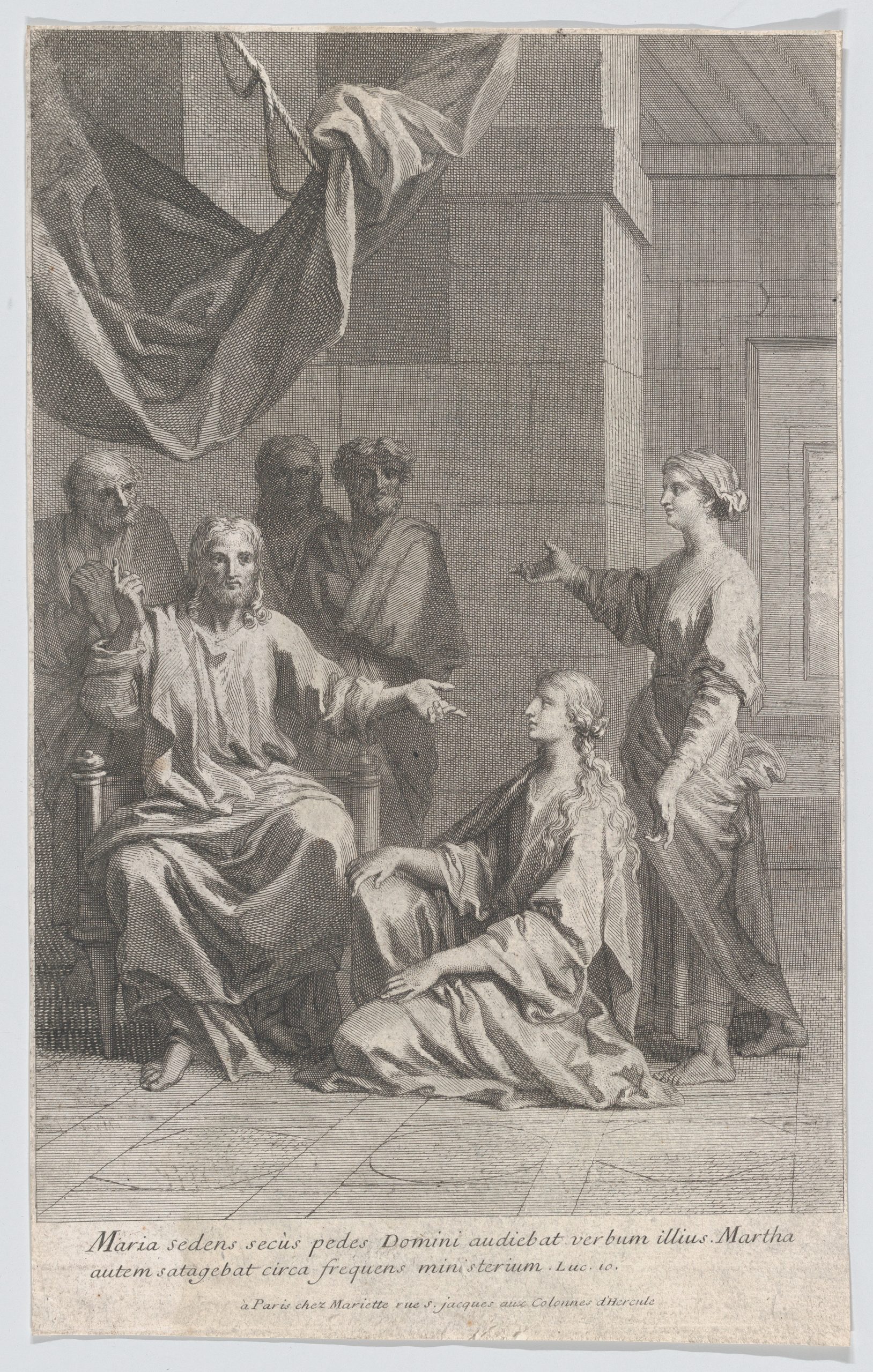

In Luke’s account, Martha invites the disciples to her home and expresses hospitality toward them by tending to their needs. Her sister Mary, on the other hand, sits at the feet of Christ as he teaches. Exacerbated, Martha rebukes Mary to Jesus, claiming she ought to assist her. Jesus, however, tenderly responds to her criticism, stating that Mary has chosen the better path.

In John’s account, after Lazarus dies, Martha acknowledges Jesus’s power: Lazarus would not have died if Jesus was there, but God will grant all that Jesus asks (11:21). After Jesus proclaims that he is the resurrection and the life, Martha responds emphatically with a strong, Christological claim: Jesus is the Messiah, the Son of God, who is come into the world. After Jesus raises Lazarus from the dead, a dinner is served in his honor. Like Luke’s account, Martha serves inside, and Mary sits at the feet of Jesus. However, here Mary anoints his feet, wiping them with her tear–filled hair.

Mary and Martha are sometimes pitted against one another; Mary is relaxed while Martha is a busybody. However, both expressed aspects of discipleship and provide a paradigm for all Christians to follow. Mary expresses worship in Luke’s account by listening to Jesus teach, and in John’s account by anointing Jesus’ feet. Martha’s devotion is through hospitality, which certainly was not contrary to the way of Jesus. In John’s account, she serves those in attendance for the dinner in Jesus’ honor. Jesus receives this service. Though in Luke’s account Jesus gently corrects Martha’s behavior, this is not a blanket scolding of her behavior: her service was good. Such service is recognized throughout scripture, such as when Zacchaeus welcomes Jesus in Luke 19:1–10.2 In that particular moment, however, Jesus reminds Martha of the importance of intimacy with him.

Earlier Christians believed both women embodied discipleship, and gender did not convolute their interpretation. Origen (c.185–c. 253) argued that Mary and Martha’s actions are not contradictory but represent two facets of the Christian life: contemplation, which influences action, and vice versa. Fourth and fifth century monastic interpreters, though often favoring Mary, typically viewed both of these women in a positive light, and some even favored Martha in Luke’s account. For patristic preachers, though coming to different conclusions on how to apply this story to Christian living, gender was not central to their interpretive lens. They agree, however, that their stories are relevant to women and men alike, modeling discipleship for all. In the medieval era, both women were given legendary backstories: Mary was a preacher, while Martha was a miracle worker and dragon slayer.4 Though not in the text itself, this extrabiblical story displays the influence these women had on Christians. Taken together, Mary and Martha model a robust view of discipleship: sitting at the feet of Jesus and listening to all he teaches, and through the outpouring of his love, serving those around us.

Sources:

• Jennifer Wyant. Beyond Mary or Martha: Reclaiming Ancient Models of Discipleship. Atlanta: SBL Press, 2019.

• Beth Allison Barr. The Making of Biblical Womanhood: How the Subjugation of Women Became Gospel Truth. Grand Rapids: Brazos Press, 2021.

In Luke’s account, Martha invites the disciples to her home and expresses hospitality toward them by tending to their needs. Her sister Mary, on the other hand, sits at the feet of Christ as he teaches. Exacerbated, Martha rebukes Mary to Jesus, claiming she ought to assist her. Jesus, however, tenderly responds to her criticism, stating that Mary has chosen the better path.

In John’s account, after Lazarus dies, Martha acknowledges Jesus’s power: Lazarus would not have died if Jesus was there, but God will grant all that Jesus asks (11:21). After Jesus proclaims that he is the resurrection and the life, Martha responds emphatically with a strong, Christological claim: Jesus is the Messiah, the Son of God, who is come into the world. After Jesus raises Lazarus from the dead, a dinner is served in his honor. Like Luke’s account, Martha serves inside, and Mary sits at the feet of Jesus. However, here Mary anoints his feet, wiping them with her tear–filled hair.

Mary and Martha are sometimes pitted against one another; Mary is relaxed while Martha is a busybody. However, both expressed aspects of discipleship and provide a paradigm for all Christians to follow. Mary expresses worship in Luke’s account by listening to Jesus teach, and in John’s account by anointing Jesus’ feet. Martha’s devotion is through hospitality, which certainly was not contrary to the way of Jesus. In John’s account, she serves those in attendance for the dinner in Jesus’ honor. Jesus receives this service. Though in Luke’s account Jesus gently corrects Martha’s behavior, this is not a blanket scolding of her behavior: her service was good. Such service is recognized throughout scripture, such as when Zacchaeus welcomes Jesus in Luke 19:1–10.2 In that particular moment, however, Jesus reminds Martha of the importance of intimacy with him.

Earlier Christians believed both women embodied discipleship, and gender did not convolute their interpretation. Origen (c.185–c. 253) argued that Mary and Martha’s actions are not contradictory but represent two facets of the Christian life: contemplation, which influences action, and vice versa. Fourth and fifth century monastic interpreters, though often favoring Mary, typically viewed both of these women in a positive light, and some even favored Martha in Luke’s account. For patristic preachers, though coming to different conclusions on how to apply this story to Christian living, gender was not central to their interpretive lens. They agree, however, that their stories are relevant to women and men alike, modeling discipleship for all. In the medieval era, both women were given legendary backstories: Mary was a preacher, while Martha was a miracle worker and dragon slayer.4 Though not in the text itself, this extrabiblical story displays the influence these women had on Christians. Taken together, Mary and Martha model a robust view of discipleship: sitting at the feet of Jesus and listening to all he teaches, and through the outpouring of his love, serving those around us.

Sources:

• Jennifer Wyant. Beyond Mary or Martha: Reclaiming Ancient Models of Discipleship. Atlanta: SBL Press, 2019.

• Beth Allison Barr. The Making of Biblical Womanhood: How the Subjugation of Women Became Gospel Truth. Grand Rapids: Brazos Press, 2021.

Title of Art: Christ in the House of Martha and Mary

Subjects: Mary, Martha, Jesus

Subject Century: 1st

Artist: Unknown

Art Form: Illustration

Date of Composition: 18th century

Exhibit Institution: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Exhibit Location: New York, NY

VM Image #: 0123

Photographer: Public Domain